The Modern Myths of Creativity: What is and what is not

It is increasingly common to read on social media about Creativity.

Being a theme with increasing importance, it is not difficult for many professionals to talk about Creativity to explore this new demand or simply to make their content more attractive.

However, in the race for the need to develop it, those who chose to explore Creativity in its contents seek an easier way for their audience to understand the creative phenomenon, resulting in misfits or incomplete statements of what Creativity is.

It may seem harmless at first, but a lie told several times becomes a truth, even more so if it is told by “experts”. This without adding to the fact that people share content without checking the information. I think now it is possible to understand the seriousness of the situation.

“The biggest obstacle to discoveries is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.” — Daniel Boorstin

The study of Creativity exists officially for almost a century. Therefore, for those who really seek to understand it, it is necessary to know its origins and characteristics.

THE MYTHS OF CREATIVITY

Some beliefs about Creativity are part of common sense, which we have been passively induced to believe. Here, the term myth is used to refer to the confusion of the understanding of Creativity by these beliefs.

Most people still believe in the ancient myths of Creativity, where these myths are nothing but old definitions of what was believed to be the creative manifestation.

However, with the business attention turned to it and with the increase of professionals talking about the topic, new myths have emerged that need to be clarified.

MODERN MYTHS

These new myths are repeated as mantras by more and more “experts”, perpetuating misinformation. I called them Modern Myths of Creativity.

The biggest problem with modern myths is that they are made up of half-truths. They only address part of what Creativity really represents, and that is why they become so tempting to believe.

As propaganda vehicles, half-truths are excellent, as they capture our attention and generate a sense of urgency and scarcity. So, we can say that:

“The most brilliant of propagandistic techniques will not bear any fruit unless a fundamental principle is always kept in mind — it must be limited to a few ideas and repeated over and over again”.

It makes sense, doesn’t it? Who said that knew how to sell an idea: it is an excerpt from Mein Kampf, by Adolf Hitler.

Of course, not all “experts” have Machiavellian intentions; they are just reproducing what they heard. However, for those who do not seek knowledge but only an immediate solution, a half-truth is more than enough.

MODERN MYTH # 1: CREATIVITY IS A SKILL

Creativity is constantly classified as a skill, especially after the World Economic Forum report puts it on the list of the ten most important skills for the future (the so-called Soft Skills).

However, Creativity is not a skill, but a competence.

Competence and skill are two concepts that are related, since skill is the ability that a person acquires to perform a certain role or function, while competence consists of the combination and coordination of skills with knowledge and attitudes.

Roughly speaking, we can summarize it as:

· Skill = Something you don’t know and learn how to do

· Competence = Something you do intrinsically, but you can develop to do it better

In other words, we develop competence by training and/or acquiring the necessary skills, knowledge, and attitudes.

A good example is to relate Creativity to Breathing:

· Breathing: we all breathe, but it does not mean that we explore the full potential of our breathing, being able to learn to breathe better through techniques and concepts.

· Creativity: we all create, but it does not mean that we explore all of our creative potential, being able to learn to create better through techniques and concepts.

“Knowledge is knowing what to do, Skill is knowing how to do it, Competence is realizing it.” — João Alberto Catalão

However, skills and knowledge we all have. The key piece here is attitude.

Creativity is not, for example, thinking differently; it consists of preferring to think differently, having the courage to think differently, or even having the habit of thinking differently.

(Note: the definition of competence is not the definition of Creativity. I will talk about it in Modern Myth #5.)

MODERN MYTH # 2: CREATIVITY IS A TOOL

You have probably heard that Creativity is “a tool for solving problems”, right? Wrong.

Same as skills, tools symbolize just one piece in the Creativity’s puzzle. They are components that can help you (or not) achieve your goals.

To better understand this issue, the Guilford’s Alternative Use Test (1967) proposes that the individual suggests the greatest possible number of uses for a brick. In this case, the brick is the tool, and how you use it depends on your ability to think creatively.

Of course, a brick is a physical tool. If your challenge is conceptual, you will need conceptual tools; however, the process is the same.

For example, you can use Brainstorming for generating ideas, Convergent Thinking to select the best ideas, and Six Thinking Hats for validating them. You can use these tools in conjunction with other tools. Or you will not use any tools at all and arrive at a creative result anyway.

That is, the tools will help you with a specific task, assuming that you know how to use it.

“When a photographer masters the tools and processes of the art, then the quality of the work is only limited by his creative vision”. — Edward Weston

To make it clearer, we can organize the elements in the following order (from the simplest to the most complex):

Tools > Skills > Knowledge > Attitudes > Competence

As a competence, Creativity is present in the way you choose to combine and coordinate your skills, knowledge, and attitudes to formulate and concretize your ideas. It is basically like a DIY job; the more skills and tools we have at our disposal, the greater the possibilities of bringing them together and coordinating them in a creative way.

(Note: the definition of competence is not the definition of Creativity. I will talk about it in Modern Myth #5.)

MODERN MYTH # 3: CREATIVITY IS SOLVING PROBLEMS

“Creativity is a tool for solving problems”. We have already clarified that it is not a tool, now we will clarify the rest.

Problem-solving is related to Creativity when it comes to finding creative solutions to questions or dilemmas, but it does not mean that to solve problems you must be creative. For example, in mathematical problems, it is possible to solve them without using a single drop of Creativity.

How much is 2 + 2? 4. Done. No need for Creativity here.

Of course, complex problems like global warming or the pandemic would be a little more complicated to solve without Creativity, but it is not impossible. By mastering the right tools, skills, knowledge or attitudes, you can arrive at a satisfactory solution. But, if you want to solve the problem with Creativity, it is necessary, among other things, to know how to bring together and coordinate all the elements.

“For me, Creativity includes problem-solving. That’s the broad definition of it”. — Edwin Catmull

But there is a clear difference between the two:

· Problem-solving: has a specific objective, presented in a logical order, and with a systematic approach to be solved.

· Creative process: there is not necessarily an objective, and it can be guided by intuition or guess, and the use of unconventional models of thought is common.

In this sense, problem-solving is less complex and can be an element belonging to Creativity and the creative process. Considering Creativity as a kind of problem-solving does not bring any benefit to your understanding.

MODERN MYTH # 4: CREATIVITY IS TO HAVE NEW / ORIGINAL IDEAS

The essential element of the novelty appears in almost all definitions of Creativity, being one of the central properties of the creative phenomenon.

No novelty = no creativity.

However, the novelty is not enough on its own, if not any deviation from the usual could be considered Creativity. But here is the catch: what is really new?

This difficulty in definition occurs because, when we discover something that had already been discovered by someone else, this does not cancel out the fact that it is still a novelty for us.

A great example of this is the selfie stick. First invented in the 1980s by Japanese engineer Hiroshi Ueda, the idea came after a frustrating experience on his trip to Europe with his family. Despite having solved the problem, the invention was listed as one of the 101 useless inventions of that time.

However, in the early 2000s, Canadian Wayne Fromm came up with the same idea as Ueda completely by chance, since he was unaware of the Japanese invention. However, unlike Ueda, Fromm was successful for a number of factors, mainly technological. The ease of taking pictures and the massive use of social media to share them at the beginning of the millennium made the process of taking selfies much more attractive.

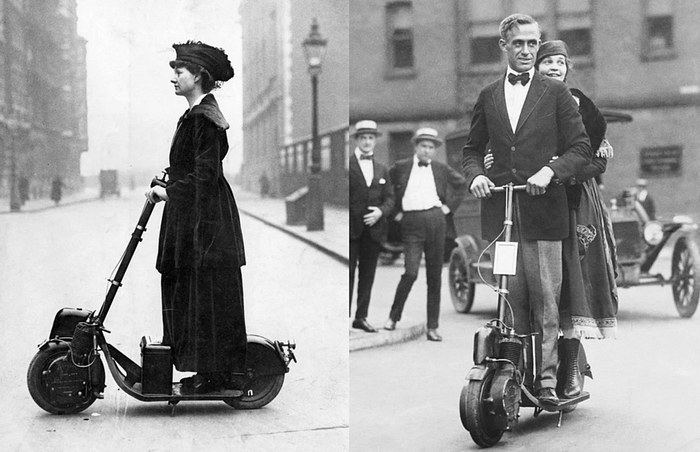

Another excellent example is the electric scooter. Created in 1915 under the name of Autoped, rapidly won the hearts of its users as a luxury item, but it eventually lost credibility as it was too disruptive for the time and was considered “more expensive than a bicycle and less comfortable than a motorcycle”. However, more than a century later, the electric scooter is back, populating the streets of the largest cities in the world, with no clue if they will disappear again or if this time it is back for good.

Of course, these are not isolated cases. I could mention Leonardo DaVinci’s inventions or Jules Verne’s literary creations. More recently, the ideas of Nicola Tesla, the Memex personal computer or even ambitious projects by Google and Elon Musk.

The new means that which has never been manifested before, but also, the emergence or attribution of a new meaning. In order for a new meaning to emerge, it is necessary to consider the context of the creative act, as this context is a fundamental factor in the definition of this new meaning.

“It is not important to see what no one has ever seen, but to think what no one has ever thought about something that everyone sees.” — Arthur Schopenhauer

In addition, too much novelty can also undermine your Creativity. However, it is not enough just to be something new, it is necessary that the result of this creation, in addition to being new, offers some new social or personal value, and this creation may also be considered useful, appropriate or effective.

In short, the element of novelty in Creativity depends on where that creation is inserted and contextualized. The new will then depend not only on what is created, but also on where and why it was created, adding value and meaning to individuals and / or the environment where they find themselves.

MODERN MYTH # 5: DEFINITION OF CREATIVITY

There is not exactly a specific belief here. Quite the contrary: if we look at the definitions of Creativity out there, Creativity can be basically anything.

Furthermore, although Creativity is a competence as I said earlier, the definition of competence is not the same as the definition of Creativity.

With almost a century of study, several researchers have dedicated their lives to finding this definition and better understand the creative phenomenon, so imagine how hard it is to listen to the nonsense people say about Creativity.

In 2004, researchers analyzed several definitions of Creativity present in academic articles, in order to find common points among them and propose, once and for all, a more… well, definitive definition. The conclusion of this study was:

“Creativity is the interaction among aptitude, process, and environment by which an individual or group produces a perceptible product that is both novel and useful as defined within a social context.” — Plucker, Beghetto e Dow (2004)

Is that the only accepted definition of Creativity? Certainly not. However, we cannot confuse the existence of different definitions as “lack of consensus”, because it is just the opposite: this demonstrates that it is possible to propose a definition of Creativity in a greater or lesser degree of elaboration.

The definition by Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow (2004) does not conflict, contradict, or compete with any other definition, especially because it was the result of the analysis of dozens of definitions. But, as you can see in the study, all definitions agree that certain elements are essential for Creativity.

MODERN MYTH # 6: WE ARE ALL CREATIVE

This myth is related to the myth of skill, since it is contradictory to state in the same sentence that Creativity is a skill and that everyone is creative. If skill is something you don’t know and need to learn, there is no way everyone can be creative, as there will always be those who haven’t learned it yet.

The same goes for the myth of tool. Like the skill, we have several tools that we don’t know how to use. Thus, considering Creativity as just another tool makes it impossible to say that we are all creative.

But that’s not just why claiming that we are all creative is a myth. We have two distinct reasons:

The first reason is: Creativity is action, it is a verb, it is movement. There is no Creativity in inertia. To be creative, you need to practice, do, CREATE. No one can be creative if they are not creating. That is, we are only creative when we create.

Creativity without action is just an idea.

And the second reason is: Creativity is not omnipresent. You can’t be creative all the time and everywhere. We are creative in certain areas, because it depends on how well we master those subjects.

Without wisdom and knowledge there is no Creativity.

References

Zamana, F. & Toldy, T. (2020). Creativity Guidelines: building creative thinking. Iberoamerican Journal of Creativity and Innovation, 1(1), pp.04–12.

Albert, R. e Runco, M. (1999). A History of Research on Creativity. In: Sternberg, R. (Ed.). Handbook of Creativity (pp. 16–34). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Boorstin, D. (1992). The Creators: A History of Heroes of the Imagination. New York, Image Books.

Cramond, B. (2008). Creativity: An International Comparative for Society and the Individual. In: Morais M. e Bahia S. (Ed.). Criatividade: Conceito, Necessidade e Intervenção (pp. 14–40). Braga, Psiquilibrios Edições.

Cropley, A. (2016). The Myths of Heaven-Sent Creativity: Toward a Perhaps Less Democratic But More Down-to-Earth Understanding. Creativity Research Journal, 28(3), pp.238–246.

Cohen, L. (2012). Adaptation and creativity in cultural context. Revista de Psicologia, vol.30 (nº1), pp.5–18.

Dacey, J. (1999). Concepts of creativity: A history. In: Runco, M. e Pritzker, S. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of creativity, vol. 1 (pp.309–322). California, Academic Press.

Guilera, L. (2011). Anatomia de la Creatividad. Barcelona, Fundit.

Harari, Y. (2017). Sapiens: História Breve da Humanidade. Amadora, Elsinore.

Harari, Y. (2018). 21 Lições para o Século XXI. Amadora, Elsinore.

Hoffman, W. (1997). The Triumph of Propaganda: Film and National Socialism, 1933–1945. Providence, Berghahn Books.

Johnson, S. (2012). De onde vêm as boas ideias. São Paulo, Editora Zahar.

Kauffman, S. (2016). Humanity in a Creative Universe. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Kleon, A. (2012). Steal like an artist: 10 things nobody told you about being creative. Nova York, Workman.

Kneller, G. (1965). Arte e Ciência da Criatividade. São Paulo, Ibrasa.

Mansky, J. (2019). The Motorized Scooter Boom That Hit a Century Before Dockless Scooters. [online]. Available at <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/motorized-scooter-boom-hit-century-dockless-scooters-180971989/>.

Paul, E. e Kaufman, S. (2014). The Philosophy of Creativity: New Essays. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Plucker, J., Beghetto R., & Dow, G. (2004). Why Isn’t Creativity More Important to Educational Psychologists? Potentials, Pitfalls, and Future Directions in Creativity Research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), pp.83–96.

Sawyer, K. (2006). Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. Nova York, Oxford University Press.

Steinberg, R. (2006). The Nature of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, vol.18 (nº1), pp.87–98.

Venema, V. (2015). How the selfie stick was invented twice. [online]. Available at <https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-32336808>.